I’ve been dreaming up some alternatives to baits and sprays as strategies for controlling this backyard orchard pest.

The previous post in this three-part series looked at the more traditional methods for controlling Queensland fruit fly: orchard inspections, netting, traps and baits. I’m still tossing up whether any of them are right for me or whether I’ll just let Queensland fruit fly run rampant on my property (more on why I’m considering letting them run rampant here).

My short summer growing season makes it difficult to grow tomatoes, but the silver lining is that the bloody fruit fly doesn’t run riot for long before the cold weather shuts it down. The pain that Queensland fruit fly can inflict on the Melbourne based home gardener is phenomenal. I can see why folks in warmer climates tear their hair out when they discover this pest in their backyard orchard. But here, in my cool temperate climate, their window for destruction is short.

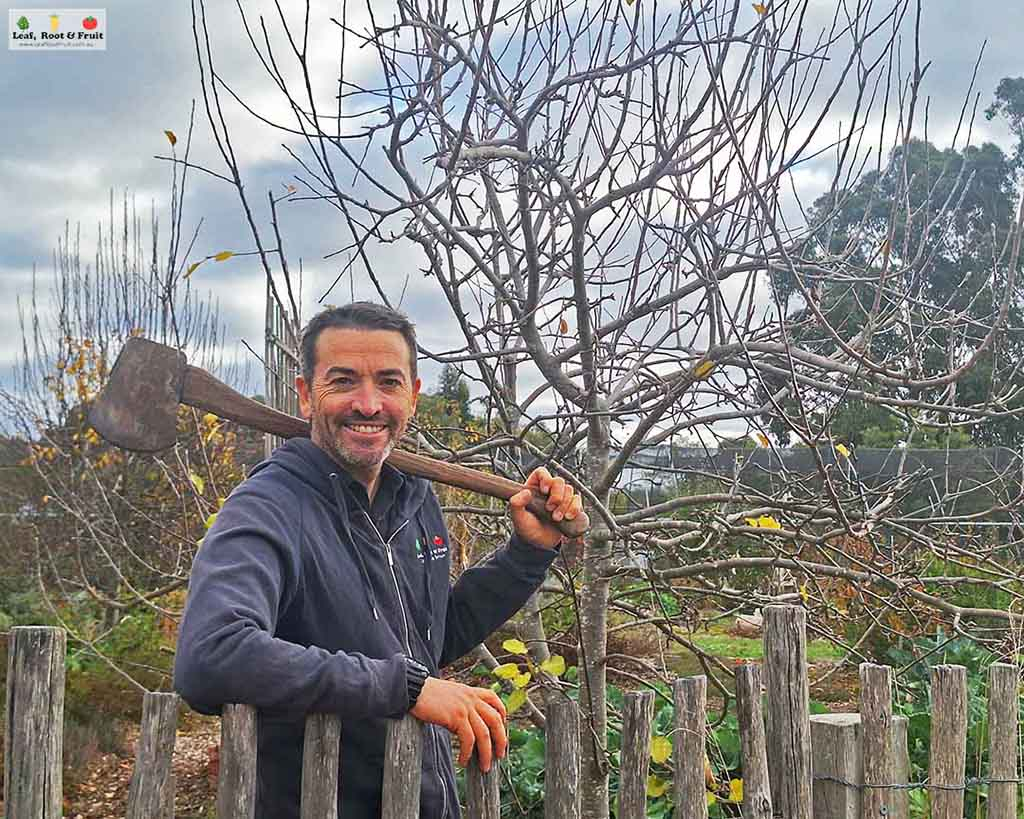

Regardless, I’m concocting a few alternative control strategies to minimise the damage they inflict on my fruit. Some involve tweaks to my orchard design. Others require adjusting my harvest strategies. And some are drastic – chop chop!

A stop in play?

Could I put a pause on my Queensland fruit fly outbreak every year? Our property is on the outskirts of town. Some of the neighbours do grow fruit trees and susceptible vegetables such as tomatoes. But there are reasonable distances between us. According to page 42 of Fruit Fly Management for Fruit and Vegetable Growers, fruit flies can move over large distances, but a 200- to 400-metre-wide buffer of open fields and no trees can be enough to reduce spread from orchard to orchard. My property doesn’t quite meet those guidelines, but it is far more isolated than a suburban garden. This is especially the case during hot and dry summers, because the flies need humidity to survive and fly.

Could I provide a big reset in my orchard by removing any trees whose fruits typically ripen in the first month or so of the typical Queensland fruit fly outbreak? I don’t have a lot of trees that ripen in mid-January because usually we are away on holidays at that time, and I prefer our house sitters to be able to relax rather spend all their time picking and preserving fruit. Saying goodbye to “Moorpark” apricots and “Royal Gem” nectarines could provide a break in the fruit fly lifecycle and reduce the height of the population curve. I like both fruits, so I’ll hold off for another year or two before swinging the axe.

Tree removal: less is more

All that fruit inspection is hard work. It’s got me rethinking how I design orchards for future clients. Sometimes clients with plenty of space ask me to design orchards with dozens of fruit trees. I’ll negotiate a more sensible number to encourage better orchard hygiene. I don’t want them to become sources of annual neighbourhood infestations. Less is more.

In my own orchard there are many fruit trees planted by the previous owner that are outside my netted enclosure. Some of the trees are wonderfully productive with tasty and delicious fruit. Other trees produce bitter cider apples, crab apples or even perfectly tasty fruit that is surplus to what I need. Some years I net these trees, other years I leave them to the cockatoos and rosellas.

My approach in the past has been that they are fine as ornamental trees that just happen to produce fruit. Now I view them as potential hosts for Queensland fruit fly. Unmanaged trees like this also attract vermin and are not a natural part of a parrot’s diet. They can have negative consequences. This winter I removed many of the surplus trees to help balance the ecosystem and reduce my orchard inspection workload.

Less is more.

Sacrificial crops

In both years of Queensland fruit fly outbreaks on my property, my “Chojuro” nashi tree was badly affected. Last autumn over half of the fruit had maggots.

What’s more, no one in our family really eats these particular fruit. I planted the tree after a family taste test of different nashi pears. At the time both my partner Caryn and my son Angus said they preferred the sweetness of the “Chojuro”. However, since that tree was established, they’ve decided they prefer other nashi varieties. The “Chojuro” hits peak ripeness in a very short window. The fruit quickly becomes soft and squishy and loses any appeal it once had (“Ya Li” is a much better choice).

On paper this tree doesn’t have a lot going for it. It’s a favourite of the Queensland fruit fly, but not preferred by my family. Back in March I was determined to remove the tree and replace it with something else. But mine is espaliered, and it has a fantastic shape.

For now, I’ve decided to let the tree live as a sacrificial tree. Given that it is a mecca for Queensland fruit fly, I’ll strip the fruit from the tree just as the annual infestation peaks and freeze the lot. Better those pesky maggots destroy a crop we’re not that interested in than, say, my precious greengages.

Resilient ecosystems have a role to play

Everything is food for something else – the food web is interconnected.

- Ladybirds eat aphids and whitefly.

- Spiders eat moths and earwigs.

- Earwigs eat codling moth eggs.

- Frogs eat slaters and slugs.

- Echidnas eat ants and termites.

- Snakes eat frogs and mice.

- Kookaburras eat snakes, frogs and mice.

Queensland fruit fly, too, is food for something. Generalist predators such as spiders, praying mantids, predatory wasps, assassin bugs and insectivorous birds are all going to enjoy chowing down on the adult flies as they zip around the garden looking to sting my precious fruit. The more predators I can encourage into the garden, the more pressure they’ll place on the fruit fly population.

A healthy, resilient ecosystem won’t prevent Queensland fruit fly outbreaks, but it will help reduce the severity of them. It’s the cornerstone of controlling every garden pest in my garden. Read about healthy garden ecosystems here.

Chickens

Allowing chickens to forage under my fruit trees could reduce the severity of fruit fly outbreaks. As they scratch about, the chickens should disturb (and hopefully eat) Queensland fruit fly pupae and maggots. However, this is going to be challenging to implement:

- Chickens and fruit trees generally don’t mix for extended periods of time. Left to their own devices, chickens will excavate huge areas under fruit trees. They can damage root systems, which can lead to long term problems with suckering. I don’t want chickens co-existing with my fruit trees all the time.

- The timing of foraging is going to be critical. I’ll want to have the chickens doing their thing just as the fruit is ripening (that’s when any maggots I’ve missed as part of my inspection program will emerge). Winter is when I typically allow my chickens into my orchard to forage and clean up any overwintering pests. But when it comes to Queensland fruit fly, Kyneton’s cool winter temperatures should kill off all maggots and pupae and put a huge dint in the adult fruit fly population. To have an impact, I’ll need to allow the chickens to forage in the orchard from February through to April.

- My chickens don’t tend to touch intact apples. But they’ll happily destroy anything with holes in it. They’ll also eat every stone fruit or ripe pear they can access. Allowing chickens in my orchard from February through to April is going to result in some large losses of fruit. If I implement this strategy, the losses caused by chickens will probably be greater than the losses fruit fly have thus far caused.

Read more about integrating chickens into backyard orchards here.

Thinking about chickens like this has made me aware of a likely silver lining to all the blackbirds in my garden and their habit of relocating mulch. The blackbirds are searching for invertebrates and worms in the mulch. They could be cleaning up some Queensland fruit fly pupae in the process. I’ll still curse them, though, every time I need to put the mulch back on the garden beds after they’ve flicked it all over the gravel paths.

Any approach to controlling pests should involve a range of methods and orchard design features. I won’t be relying on one single method such as netting or trapping. Combining a range of strategies will help ensure greater success and more fruit harvested.

That’s enough about Queensland fruit fly. I’ll get back to you with an update when I’ve got something new or relevant to share. For now, it’s time to get stuck back into gardening.

This is part three in my series on Queensland fruit fly. You can find the other parts here:

Queensland Fruit Fly Part One: Know Your Enemy

Queensland Fruit Fly Part Two: Queensland Fruit Fly Control Strategies

For those looking for hope, Eileen’s Queensland Fruit Fly Success Story is a great read.

I let fruit fly run rampant, so that you don’t have to. Paid subscriptions enable me to undertake careful research to share with you. Subscribe now for access to all the results.