Start seeing your outdoor space as an ecosystem rather than a garden

The more I learn about edible gardening, the more I learn the importance of bugs in successful gardening. Often, we are too busy concentrating on day to day gardening tasks to see that pest issues come and go in our own gardens. We see aphids today, aphids tomorrow and aphids the next day. We feel there is a problem that is not resolving itself, and we reach for a quick fix.

When performing ongoing maintenance for our clients, and visiting their gardens every two weeks, it’s a perfect time frame to see the ebbs and flows of pest predator interactions.

Good Bugs and Bad Bugs

The concept of good bugs and bad bugs is not a new one. However, in this article I’ll try to convince you that there’s no such thing as a bad bug! Instead we need to look at our gardens as ecosystems that contains a species rich diversity. All of these bugs should interact to achieve a “balance”.

Traditional “Bad Bugs”

Most “bad bugs” are labelled so, because they feed on, and damage plants in the garden. They are usually sap sucking insects, or leaf chewing insects. This damage weakens the plant, reduces the potential yield and may even kill the plant. Sap sucking insects can also transfer diseases such as mosaic virus between plants. Some of these bad bugs include:

Earwigs

Earwigs chew holes in leaves. They cause damage especially to fresh young fruit tree leaves in spring. They also have a liking for bean seedlings, lettuces and broad beans. We’ve outlined some traditional earwig control methods in a blog post.

Earwigs are also the great decomposers in the garden and as discussed below this is a silver lining to a perceived problem.

Slugs & Snails

Slugs lay their eggs in soil and emerge to feast on tender young seedlings. They are often prevalent during and after rain.

Traditional methods of control for slugs and snails are snail pellets and beer traps.

We’ve noticed that using sugar cane mulch attracts slugs and snails into the garden. This is because the sugar cane is full of sugar and yeasts, and these are the very same things that attract the slugs and snails to beer traps. The sugars and yeasts also attract the snails and slugs from the mulch into your patch.

Aphids

Aphids are profusely breeding, sap sucking insects. There are many different species, some of which have specific hosts such as the Allium Aphid (Neotoxoptera formosana) and the Cabbage Aphid (Brevicoryne brassicae). They are tiny and can be green, grey, brown and black in colour.

Aphids quickly breed up via asexual and sexual reproduction. The adult stage of the lifecycle has wings enabling them to fly (often with the assistance of the wind) to infest nearby plants.

Aphids can transport plant viruses between plants and are often accompanied by ants (see below)

Whitefly

Whitefly is another sap sucking insect that can be noticed as clouds of white insects lofting from plants as they are disturbed. They cause speckled damage to leaves. Population explosions can be greater in some years than others, depending on the local weather conditions. See some traditional control methods in our blog post.

White Cabbage Moth

White cabbage moth cause lots of damage to winter brassica crops. It is the small, green caterpillar that causes the damage by chewing holes in the leaves of plants. Small seedlings are most susceptible to damage and entire crops can often be wiped out by this pest. We’ve written an extensive blog post on control methods for white cabbage moth.

Scale

Scale are a sap sucking insect often found on citrus trees and other plants. They are waxy and difficult to control with sprays. We’ve noticed that scale tends to infect weakened trees (eg citrus trees that haven’t been fertilized for a while). They are often accompanied by ants (see below)

Ants

Ants aren’t what we would normally call a garden pest or “bad bug”. However, they are often associated with bad bugs such as scale and aphids. This is due to a symbiotic relationship that they share.

Sap sucking insects such as aphid and scale don’t have actively moving mouth parts. This means they don’t actually “suck” the sap out of the plant. Instead they insert their proboscis into the vein of the plant and use capillary (wicking) action to extract the sap. The sap flows up through the proboscis and some of the sugars from the sap are extracted as they take it up. To enable the capillary action to flow, they excrete the rest of the sap out through their “bottom” as honeydew.

This honey dew is rich in sugar and the ants greedily use it as a food source. In return the ants protect the scale and/or aphids from predation. Ants have also been observed moving the scale and aphids around the plant to encourage their spread. They effectively “farm” the sap suckers.

Ants are a symptom of a pest infestation, but not a cause of damage to the plants themselves.

What are some of the Traditional "Good Bugs"?

Lacewings

Lacewings are very generalist predators and control aphids, scale, whitefly, mites, mealybugs and all manner of sap suckers in the garden.

Their larvae, called ‘antlions,’ will eat massive numbers of pest critters over their lifetime. They can be difficult to spot as they use debris such as dust and aphid exoskeleton to cover their back as a disguise.

You may notice the eggs of the lacewings in and around your garden. I often spot them stuck to dark objects such as black plastic pots. The tiny eggs are held on with thin stalks to stop ants from predating on them.

Ladybirds

Ladybirds are one of the most commonly known “good bugs” in the garden. There are many different varieties that you might find in your garden. Most of them are beneficial and eat anything from aphids and whitefly, through to fungus such as powdery mildew.

The larvae stage look nothing like ladybirds. It is this larval stage in a lot of the species, that is most useful to gardeners

Praying Mantis

Mantises are fantastic generalist predators in the garden. They’ll eat any other arthropod that they can reach. They are ambush predators, remaining stationary until prey comes within their reach, and then they strike their prey

Hoverfly

Hoverflies are often mistaken for bees or wasps due to their striped yellow and black abdomen. You’ll often find them buzzing around your garden in spring and summer.

The hoverfly larvae is a tiny, blind maggot. They move along plant surfaces looking for aphids to prey on. Once detected, they seize the aphid and digest its juices. The exoskeleton is then discarded. A hoverfly can eat up to 30 aphids per day.

Spiders

Spiders are generalist predators in the garden and help control the balance of a large variety of arthropods.

Predatory Wasps

There are all manner of predatory or parasitic wasps available to help out Melbourne based gardeners. Most of them lay the eggs under the skin of the target species. The eggs hatch inside the host species and the pupae slowly consume the host from the inside out.

Predatory wasps target all manner of “bad bugs” including aphids, caterpillars, scale, whitefly and even other wasps.

Population Dynamics

I want you to imagine for a minute that you’ve got a huge glass box.

In that glass box are unlimited lettuces.

Now we are going to introduce two rabbits to that glass box. In the absence of predators and with unlimited food, they will quickly breed up at an exponential rate.

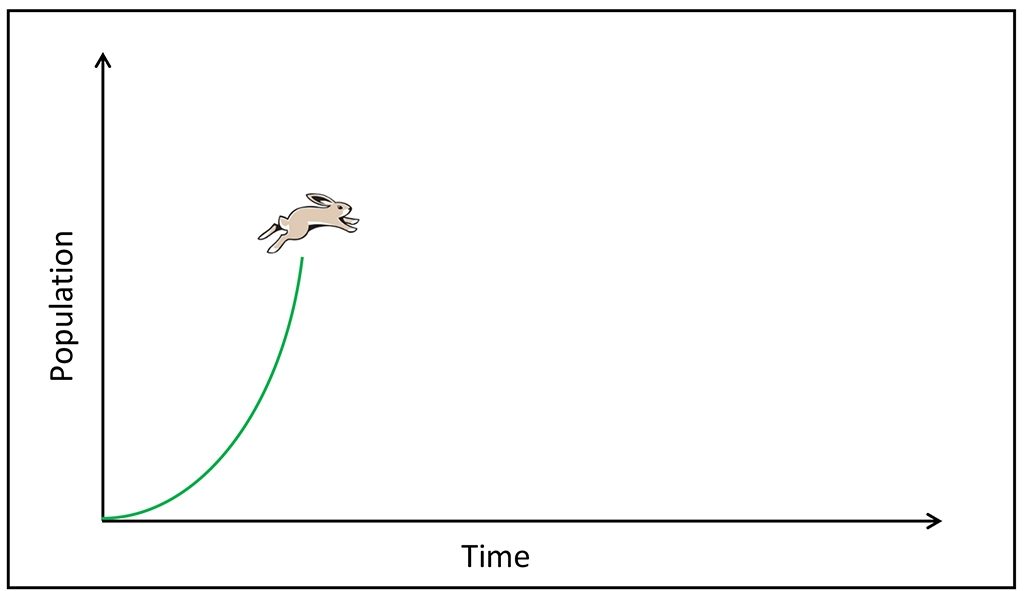

If we chart what happens to those rabbits over time it looks something like this.

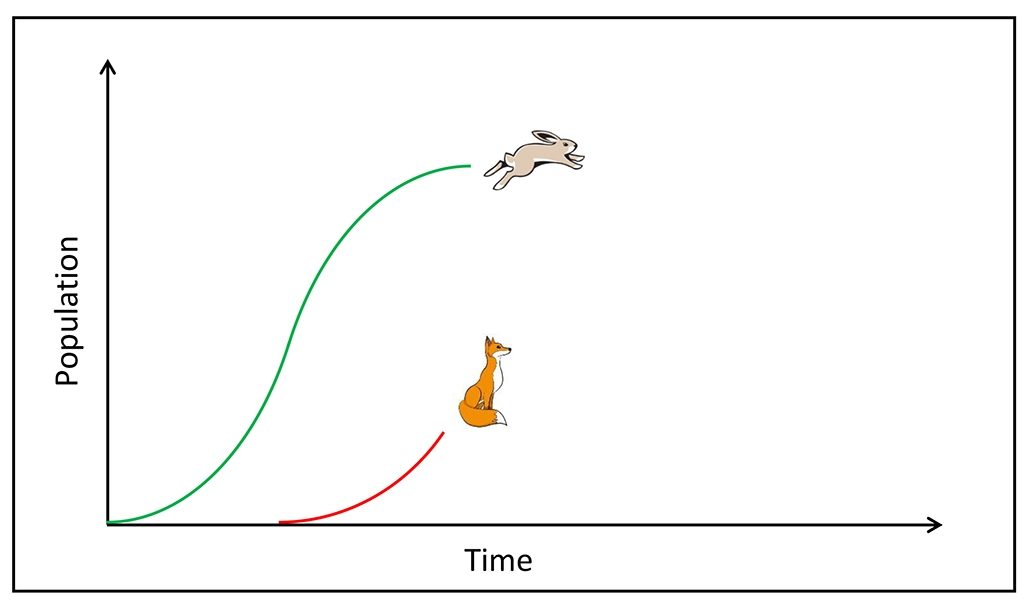

After some time, we could introduce two foxes to the glass box. They start eating the rabbits and also start breeding up in numbers.

The rabbit growth rate slows as they get eaten.

The more the foxes breed up, the more rabbits they eat. This causes the rabbit population to dwindle.

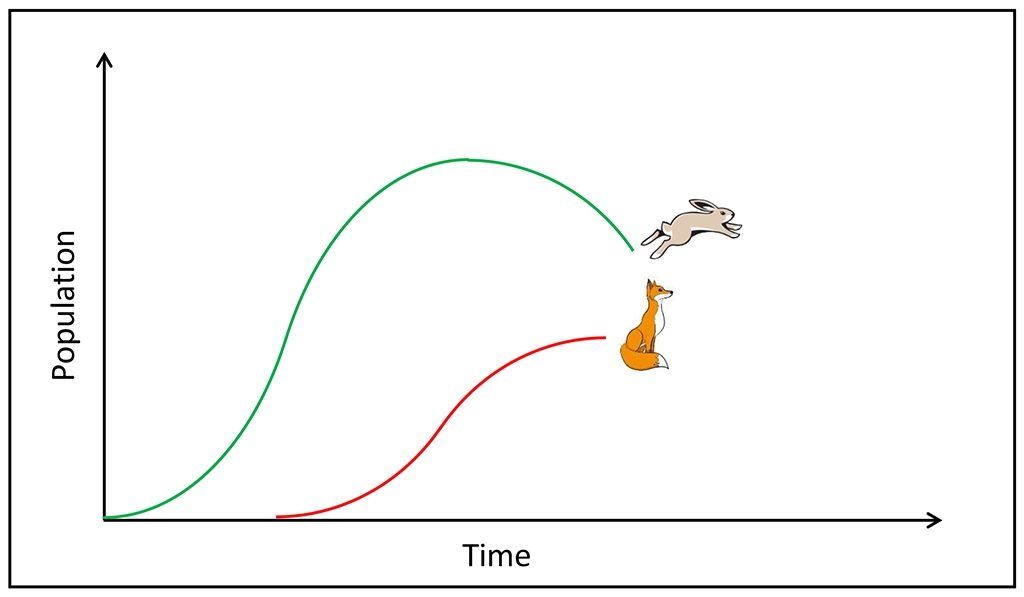

After a while, there are not enough rabbits to support the number of foxes that are in the box. So the fox population starts to crash.

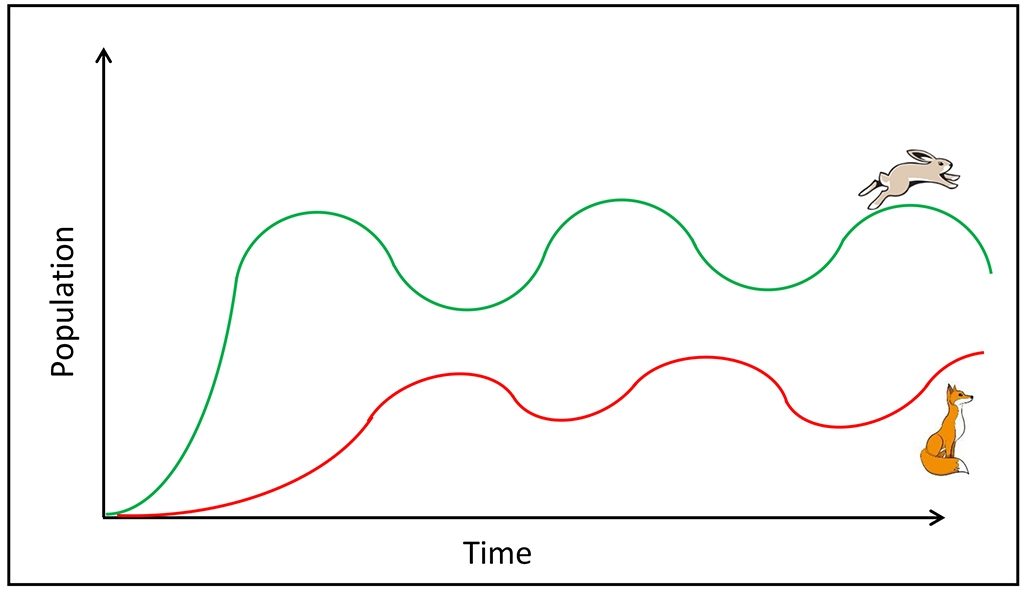

Correspondingly, with fewer foxes in the box, the rabbit numbers start to increase. This fluctuation keeps repeating in a balanced cycle.

Now if we happen to get rid of all the rabbits in the box, what happens to the foxes? Foxes have no food so they can’t exist. So our fox and rabbit population gets out of balance. The foxes cannot live without the rabbits.

Let’s change our thinking from foxes eating rabbits to ladybugs eating aphids. Here we can also see that the ladybugs and other good bugs cannot exist without the bad bugs.

So does that make the Bad Bugs suddenly “Good Bugs”?

The “Good Bugs” can’t exist without the “Bad Bugs”. So, in small balanced quantities I believe that all bugs are good. The key is to make sure that you have a diverse ecosystem and it will be resilient and low maintenance.

Unleashing pesticides in the garden is a terrible idea. Pesticides kill the beneficial insects as well as the targeted “bad bugs”. This means that the population of all the bugs in your garden will crash and you can’t obtain a balanced population dynamic. Once you start spraying, you will need to keep spraying at regular intervals to keep all bug populations low.

The best thing is to just step back and “Do Nothing”. Let nature take care of the “problem” for you!

Look for the good in the “bad”: They all have a silver lining (probably)

Most of the “bad bugs” have good sides to them, you just need to change your perspective to see the silver lining.

For example, earwigs tend to eat a lot of veggie seedlings. However, they are also nature’s great decomposers. They help break down our composts, and they help break down leaf litter. They also eat codling moth eggs. Beekeepers are introducing earwigs into their beehive to control varroa mites.

This is a photo I took a few years ago. It shows a European Wasp attacking a white cabbage moth caterpillar. I watched them for ages, slowly dissecting the caterpillar and flying it back in pieces to its nest. So the European wasp is actually helping to control another pest in my garden.

I have huge rat problems in our suburban garden. The rats eat my tomatoes, pepinos, peaches, apples, pumpkins, sweetcorn and cucumbers. It is very frustrating. However, I’ve also noticed lots of little piles of empty snail shells tucked up behind plant pots and other locations. I believe that the rats have been eating the snails and controlling that issue for me. Without the rats, we would possibly be overrun with snails in our garden.

There are so many similar examples of silver linings with your pest problems. Remember everything in life is a consumer until it gets consumed…. It’s all about balance and supporting the higher level predators.

Just Relax and “Do Nothing” Pest Control!

As humans, we tend to want to control things. Often, we direct that control to areas that we’re not quite sure of what we’re doing. An ecosystem is a complex entity that is best left to sort itself out. A well-designed garden with lots of diversity can help increase resilience and lower maintenance requirements. This leaves you with plenty of time to “Do Nothing”.

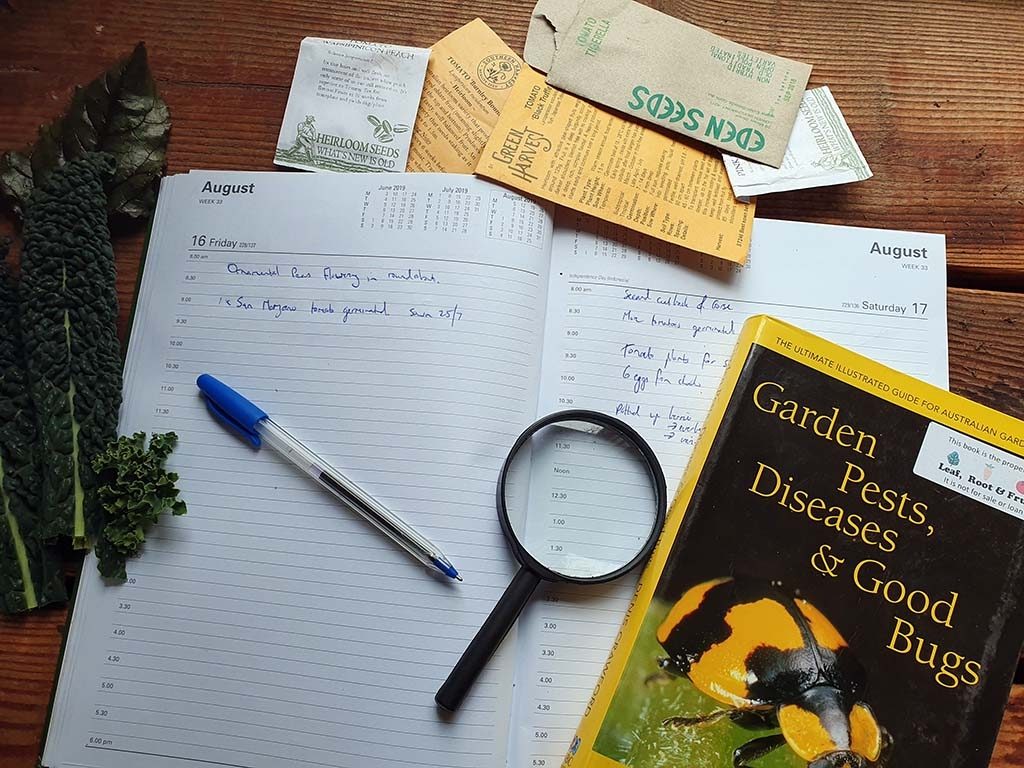

Don’t bother investing time, money and energy on pesticide regimes and pest control methods. Instead invest in a magnifying glass, and a good quality bug book. Any bug book will do.

Start identifying the bugs in your garden, and really get to know what’s going on. Keep a gardening diary and note the fluctuation in pest and predator populations. Focus on observation rather than action. You’ll soon start to see patterns emerge with the different seasons and the different species.

Stop using pesticides and try and relax and enjoy the garden. At first it takes a lot of effort to change your mind set to “Doing Nothing”. However, with practice and patience you’ll find that you have a much healthier ecosystem in your garden if you “Do Nothing”!

Just relax! Watch the fluctuations of bugs pulse in and out of balance, rather than panicking.

Spend time observing and less time doing. Spend less money on gimmicks and sprays and more time on growing flowers.

Want to know more?

The idea of “Do Nothing” Gardening will appeal to many of you. We have some great garden design tips to help create a resilient, self-maintaining ecosystem.

We have put together two other blog posts in this series:

Part Two: Attracting Beneficial Insects into the Garden

Part Three: How to turn your garden into a Resilient Ecosystem

If you would like further information on garden ecosystems, then please sign up to our Science of Edible Gardening Workshop Series. The April workshop (repeated annually) in the series focuses heavily on population dynamics and pest predator interactions.

Great post – really well explained Duncan!

Thanks for the feedback Jon!

Great article im interested to know how you control your rat population though? I have chooks so they infest the shed. If i didnt poison i would be overrun. But interesting that they eat snails. I guess mine have preferred tastes!

Hi Rhonda,

That’s very difficult to do in suburbia. But the best strategy is to reduce the food available to the rats. Ensure they cannot access compost bins. Remove any food scraps or spilt feed from the chook run each night. The treadle feeders are great in my opinion and will quickly pay for themselves in reduced feed bills.

Hope that helps

Duncan

A fabulous post Duncan…I’ve been working on my own Eco System for a while now..it takes plenty of patience. Looking forward to reading more in future Blog posts…thank you!

Thanks for the great feedback Heather.

Good Luck and Happy G

ardeningEcosysteming!White Cabbage Butterfly (Pieris rapae)

Thank you, a good reminder that everything has its place and purpose.

Glad you found it useful Janine. Good Luck & Happy Gardening!

This article is so educational! I have learnt more now built on my exiting knowledge about pest control. I also like to adopt a “Do nothing” approach, and I talk to the birds, rats and possums, in my prayer, that we live in harmony, and I ask them not to eat all my veggies. I have my chilies eaten, but they don’t touch my cucumbers. My Kales were all eaten, either by butter flies or rats. I will plant some more and net them early. Can you tell me about my peach tree, shall I spray copper spray when the leaves are falling (as the majority gardeners suggested). Many thanks for your information. Really appreciated it.

Kindest regards,

Eva Connellan

Hi Eva,

Thanks for your kind words. I don;t normally spray nectarines and peaches with copper spray as I find it is relatively ineffective. I very humid sprigs we tend treated and untreated trees suffer. In years where we experience less rainfall and more wind in the spring then all trees seem to fare much better. I prefer to avoid the sprays as the copper can also have an impact on the soil biology.

Good Luck & Happy Gardening!

Duncan

Fascinating article. I came to the site for an answer for my cottony cushion scale on my citrus trees.

What do you suggest for black spot and mildew in roses?

I live in SW France.

Bonjour Fleur,

Thanks for the great feedback. For almost every pest or disease I recommend doing “nothing” and have the same advice for your roses. The black spot and mildew are fungal infections and are being exacerbated by high humidity. Increasing airflow around the roses will help, as will growing rose varieties that are more resistant to such diseases. You can spray an anti-fungal but this will also impact your soil biology.

Good Luck & Happy Gardening

Duncan

Hello Interested in any observations on Giant Willow Aphids – had checked with beneficial insect supplier who advised he was not confident he had a suitable predator ..do nothing is not an option as somewhat overwhelming …we squash but requires constant monitoring ..thank you for any suggestions

Hi Robert,

I don’t have willow or poplar trees and have zero experience with Giant Willow Aphids. I’d imagine that many generalist predators would feast on them. If it were me, I’d be taking the patient, do-nothing approach.

I notice that most aphid outbreaks are very seasonal. Usually in spring or autumn when temperatures are mild (low to mid 20s) and humidity is high. I’ll be interested to hear if your population decreases with the drier heat of summer.

Please keep me updated

Duncan

A big statement, but this is one of the best articles I’ve read concerning the garden.

I don’t use pesticides and spend a great deal of time “fluffing about“ in my garden watching bugs, but I learnt plenty just now reading your post.

Thanks for all you do,

Jennie

WOW! That’s a huge statement. Thanks for your kind words Jennie.

Happy gardening

Duncan

Hi Duncan,

Another great post! I do love your posts – I love the science. This is still pretty rare in Gardening magazines, books and on line!

Gembrook, where we live, is ‘pest central’ at times, but we’ve found some ways of dealing with it.

One way, after trying various ‘heroic’ and expensive strategies, is certainly your Do Nothing and Observe approach; and plantings that encourage the Good Bugs have helped a lot. And as we are now in our 70’s, it suits us better too.

I gave up using a copper spray on stone fruit some time ago, as it seemed pretty ineffective (as you said) and besides, it was a pain doing it. Then I realised that it was probably killing off the beneficial soil fungi as well (Duh, it’s a fungicide!!! It takes Muggins a few goes to realise these obvious things.) So – in warm dry years we get peaches and apricots – and in wet cold years, not. That’s OK. It’s been a good year for them this year – for the first time, I’ve been able to make some apricot jam.

We had a snail plague when we moved in here – but we got some ducks, and the snails disappeared fairly quickly. Sometimes I even ask friends to bring us their snails (in Ice-cream tubs) for our ducks, and I give the friends veg, or duck eggs, in return. (They think we’re a bit weird though!)

There are quite a few slugs in the garden beds, as the ducks can’t get in there, but it’s managable by a bit of torchlight hunting or “beer” traps now and then. Ditto earwigs and slaters.

Rats have been a problem since we arrived. We thought about getting a garden tiger (cat); but a cat wouldn’t willingly sleep with the ducks every night. We got a treadle feeder: that helped a bit, and also sent packing a flock of sparrows that were helping themselves as well. We’ve tried all sorts of traps for the rats, but alas, Ms Rat now has a Degree in Trapology 101, and will not go near any of them. In fact I find that even un-set and un-baited traps will (sometimes) keep Ratty away from pumpkins, broad beans, peas and other things near ground level.

We do regularly trap her progeny, so that keeps the numbers down. We hope it’s a quicker and more humane death than poisoning.

There’s usually a bit of a cabbage grub problem in spring. I’ve noticed some brassicas are more attractive to them than others – maybe it’s the taste or smell? Or is it the health of those particular plants? When I start to see caterpillars, I gradually harvest all the un-netted brassicas – the ducks get the outside leaves; nothing is wasted.

I also note small clusters of cream coloured pupae cases (or egg cases?) on the leaves as time goes on. Plenty of butterflies about, but the caterpillar population decreased so much I couldn’t find enough of them to pick off for a duck-treat. It seems something else is eventually controlling them? maybe parasitic wasps as you say?

…but meanwhile, my Couve Tronchuda (not netted), is lace-work, and struggles to grow a few new leaves… However, we humans have enjoyed some excellent Kalibos cabbages and some small caulis which were under Vege-net.

Nothing has attacked the tomatoes, cucumbers or french beans yet, but we’re expecting the parrot population (as well as Ms Rat) to notice them soon. So it will be back to unbaited, unset traps, and a bit more netting, all round. They’re too busy eating the green hazelnuts now! Maybe the hazelnuts are just a ‘trap crop’ to protect the tomatoes?

Happy Eco-Systeming…

Hi Rose,

What a comprehensive update. Thanks for sharing your experience and adding to the chorus for “do nothing” gardening.

Happy gardening

Duncan

Hi Duncan and LRF team

Love the philosophy, and have been trying to practice it, so thanks. But no mention of Vine Hoppers as pests, yet they are in plague proportions in my Melbourne suburban edible garden, sucking the life out of almost every plant – raspberries, figs, climbing beans, even citrus shoots, and more. I have onserved them as juvenile ‘fluffy bums’ and tried to remove those by hand, and now as hordes of adults! I sprayed them off with water pressure, and in desperation, used Neem oil. Rows of them back in place next day! I am beginning to despair about growing edibles – challenging enough without these new and prolific pests. Not sure Do nothing (but observe with magnifier ) is going to work for me!

Hi Jackie,

Vine hoppers and all the sap suckers can cause short term damage. However, I think you’ll find that the population will naturally reduce in a few weeks, once predators have started to feast on them.

Even our dreaded harlequin bugs have diminished in number this summer. I did nothing to contribute to this. They’ve just found their balance with everything else.

Plants are resilient. I urge you to continue to be patient and let nature sort out the “issue” for you.

Happy gardening

Duncan