An update on this sub-tropical fruit felon’s invasion of my orchard and what I’ve so far observed and learnt.

My journey with Queensland fruit fly began in April 2024, with the discovery of maggots in my homegrown “Beurre Hardy” pears.

I was devastated.

I’d been expecting that moment since we moved to Kyneton in 2019, but I kept pretending to myself that it would never happen. Queensland fruit fly has been rife across Melbourne for more than a decade, but the cold winters and short growing seasons of cool temperate Kyneton had slowed their spread to here.

However, the flies are adaptable, and their tolerance of our cold climate has gradually increased. I was the first person I know of to detect them in our area. Once I discovered the initial outbreak I contacted everyone I’d recently given fruit to and explained what they needed to look for if they didn’t want to end up with a backyard infestation of their own (and a mouthful of maggots). Over the next few weeks, I searched my orchard daily and watched the infestation spread to other pears, nashis and then apples.

Earlier in 2025 I shared reader Eileen’s experience of dealing with Queensland fruit fly. Her story filled me with optimism. Many readers felt the same way, telling me the post lit a candle of hope during a dark time in their own Queensland fruit fly journey.

The pesky flies returned in the summer of 2024–25, and now I’ve had two summers of observing them in my orchard. While I don’t have enough practical, personal experience with this pest to write a comprehensive guide to controlling them, I do have some experience observing them. I’ve also been trained by Agribusiness Yarra Valley in best practices for preventing, monitoring and managing outbreaks.

This is the first in a three-part series on Queensland fruit fly. There’s a lot more information that I could have included in these three posts. But most of that extra information is covered elsewhere. The booklet Fruit Fly Management for Fruit and Vegetable Growers is especially helpful at explaining the Queensland fruit fly life cycle and the whole gamut of control options available.

The series of posts I’ve written is about my journey, my take on this pest and my plan for dealing with it in my orchard under the conditions specific to my property. It contradicts some of the recommendations made by Agriculture Victoria and some scientists.

Who are we dealing with?

Like me, you’ll probably find the maggots first. Lots of different caterpillars and maggots can infest fruit. Queensland fruit fly maggots have these characteristics:

- They’re carrot shaped, with a pointy end and a blunt end

- They have a black spot on the pointy end (this is the “feeding hook”)

- The maggots can jump – it’s amazing how far they can fling themselves. But this is not a reliable ID guide because only the third and final instar (developmental phase) will jump. Plus, the maggots of some other species of fly can jump.

- They have a particular knack for destroying the entirety of the host fruit. The pattern of destruction is very different from the pattern of, say, a codling moth (except in quince where the damage can look similar). Queensland fruit fly maggots regurgitate a liquid containing bacteria that break down the host fruit’s flesh into liquid. They then use their feeding hook to scoop up the pulp. This rather disgusting mechanism of feeding is why they cause so much damage to the fruit.

Queensland fruit fly has become widespread across south-east Australia. If you live in this region, once you find maggots that fit the description above, it’s most likely you have a Queensland fruit fly infestation. But there are some other species of fly that are similar. When I found maggots in my pears, I was crossing my fingers that they were anything but Queensland fruit fly. I was hopeful that instead they were:

- metallic-green tomato fly (Lamprolonchaea brouniana)

- mediterranean fruit fly (Ceratitis capitata) or

- island fly (Dirioxia pornia).

Entomologists can identify maggots using a microscope. If you aren’t a trained entomologist, then there are two other ways to be certain of a Queensland fruit fly identification:

- Genetic testing, which is quite pricey, and at several hundred dollars you’re not going to bother

- Growing the maggots out and identifying the flies that pupate from them.

Grow baby, grow

Growing maggots out and allowing them to develop into flies is relatively easy. It just takes time.

- Grab a jar and place a small quantity of moist soil or wood chips in the bottom.

- Add your maggots to the jar.

- Place some fly wire, insect netting or cloth over the top and secure it with a rubber band.

- Place the jar somewhere warm and wait.

Until the adult flies emerge for ID it’s a good idea to assume the worst and treat any infestation as though it is Queensland fruit fly.

After around two weeks the adults should emerge. My first attempt at this took a lot longer. I put this down to a few things:

- I didn’t keep the jar in a warm enough location.

- I used shredded paper, which didn’t hold much moisture, instead of soil or woodchips.

After waiting weeks and then doing further research, I moved the jar from my classroom studio to inside the house next to the fireplace. I simulated rain by misting the jar. Within days, one single adult Queensland fruit fly emerged. But that was enough. It was official: I was dealing with my most dreaded menace.

An alternative to all that waiting is to try and trap some adult flies in your garden and obtain a positive identification that way.

Note: There are many online guides to help you identify the adult flies that emerge (this one from Fruit Fly ID Australia is my favourite). Once your ID is complete, do not release the flies. Putting the whole jar into the freezer will kill the flies and allow you to more easily inspect specimens and take photos.

A downward spiral of despair

After my positive Queensland fruit fly ID, I was devastated. I lamented that I’d never be able to bite into a juicy, ripe piece of fruit ever again. From then on, every piece of fruit needed to be cut up and inspected before consumption. You may be feeling the same way. But I’ve since bounced back. I’m now far more confident with identifying infested fruit with a quick inspection of the skin. The sting holes are usually very evident, especially as the fruit approaches fully ripe.

Sting holes present differently in various fruit and are easiest to see on light coloured fruits. It’s harder to spot sting holes on dark fruits such as plums. I’ve noticed the flies tend to leave large gaping holes in plums, but I’m told they could be exit holes, not entry (sting) holes. Nashi sting holes are mere pinpricks, but they quicky develop a telltale black ring. On apples it’s harder to spot the sting holes, but as the fruit begins to stew internally, the “juice” beings to weep out the sting holes.

I’m now confident enough to chance biting into a ripe piece of fruit and munching on it while wandering around the orchard. I’m still yet to chomp down on a mouthful of maggots.

Who is this nemesis?

The first step in controlling any pest is to learn as much as you can about it. I started reading about all things Queensland fruit fly, looking for any chinks in its armour. Queensland fruit fly is a native insect that over the past few decades has migrated south from its sub-tropical home to the temperate climate of south-east Australia. It has now found its way into my cool temperate orchard. One possible explanation for this is that the species is gradually adapting to colder conditions.

There are several stages of the Queensland fruit fly life cycle where control strategies can be aimed:

- Adult females: Netting fruit trees with insect exclusion netting prevents adult females from stinging the fruit in the first place.

- Maggots: Regularly inspecting fruit and destroying infested pieces is a great way to break the life cycle.

- Adult females or males: A huge range of traps and baits can be used to monitor and even control the adult flies. These usually target either male or female fruit flies (more on this later). In her post, Eileen focuses on this third strategy.

(I cover the different control strategies in more detail in Part Two.)

A few specific aspects of the life cycle piqued my interest:

- Much of the life cycle is temperature dependant. When temperatures are cool, the maggots develop more slowly, and pupation may be delayed.

- Queensland fruit fly mating is a curious thing. Males congregate at specific mating sites (lek sites). They use pheromones to advertise this mass orgy to the females (mating pheromones are the basis of some of the trap and bait lures). The orgies occur only at sunset and only when the ambient temperature at the time is 16 degrees C or above. The male flies serenade the females. Apparently their “song” sounds like a clicking noise to us.

- Maggots, pupae and eggs typically don’t survive the cold winters of south-east Australia. Only the adult Queensland fruit fly can survive, and it does this by seeking out warm microclimates in which to overwinter. Three locations where this is likely to occur are evergreen fruit trees (such as citrus and avocados), compost bins and bays, and chicken runs. Queensland fruit fly are attracted to ammonia smells and anyone who keeps chickens will know how much a poorly tended chicken run reeks of ammonia.

- Adult flies will die after 48 hours without access to water. Low humidity also affects their ability to fly and therefore spread.

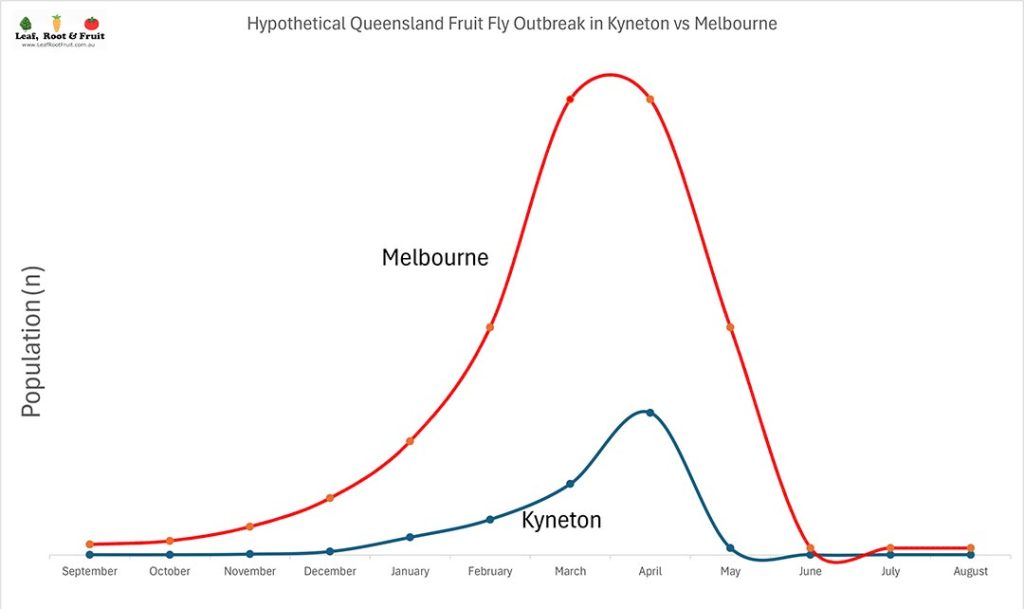

My growing season here in Kyneton is short: I plant my tomatoes late and the frost usually wipes the still very productive plants out early in autumn. The climate here appears to do the same thing to the Queensland fruit fly. The adults can’t kick start their orgies until later in the season than they can in say, bayside Melbourne. Cool autumn temperatures stop them in their tracks, so they have a much shorter season in which to breed up and damage fruit. Winter may even be harsh enough to wipe out the local population completely, and my orchard could potentially start the next spring with a blank slate. If I charted the theoretical difference between Queensland fruit fly population numbers in my orchard and their numbers in a hypothetical space in bayside Melbourne, it might look like this:

Queensland fruit fly is here to stay. We will not eliminate it. But I am hopeful that my local cool temperate climate in Kyneton will ensure that its impact on my own crops will be minimal. I may not need to do much in the way of active crop protection. Folks in warmer areas, such as Melbourne, coastal regions, northern Victoria and central NSW, won’t have the same luxury.

Another opportunity for a relaxed approach?

With every other pest I’ve come across in the garden, I’ve learnt to relax. Whether it’s codling moth or blackbirds, mice or aphids, harlequins or cabbage white butterflies, reacting to outbreaks doesn’t seem to make a big difference. Instead, I create a resilient and balanced ecosystem to minimise pest outbreaks. My netted enclosure reduces bird attack. Insect netting and timing of planting helps minimise caterpillar holes in my brassicas. Foraging chickens keep codling moth numbers low (in most years). My resilient edible forest garden helps balance out rampant pest outbreaks.

I’m not great at doing routine tasks day after day, or week after week. I’m too easily distracted by “shiny things”: the next big project. It’s why I need an automated watering system. Undertaking any Queensland fruit fly control methods that require a regular maintenance regime are not going to happen in my garden. I need a set and forget approach.

So what does this mean for old mate Queensland fruit fly? I’m possibly a bad neighbour and community member, but I wanted to see just how bad the situation could get, given that Kyneton ain’t sub-tropical Queensland, and winter should have put a big dint in their population, if not wiped them out completely. In 2025, year two of my outbreak, I didn’t bother with traps or baits. All I did was wander the orchard every few days to inspect fruit for sting holes and clean up any fallen fruit. But that’s it. No traps, no baits, and I didn’t net any of the trees inside my netted enclosure with insect exclusion netting. Outside the netted enclosure, I used insect netting to keep the parrots from stealing fruit from a few trees. Likewise, my tomatoes grow under insect netting to protect them from blackbirds and to provide a good microclimate. The insect netting prevented Queensland fruit fly from infesting these crops. But other than carrying out regular inspections, I did nothing to limit the spread of this pest.

I let fruit fly run rampant, so that you don’t have to. Paid subscriptions enable me to undertake careful research to share with you. Subscribe now for access to all the results.

So what happened?

To be honest, it was a shit show. I noticed Queensland fruit fly over a month earlier than it had appeared in my garden the year previously. The amount of affected fruit was also greater than it had been a year ago. The infestation spread further than my netted enclosure and I found maggots in a few lemons in my citrus grove. It had me reaching for the panic button: “Argh! Something needs to be done!”

But then I took a mental step back. Anecdotally, there were more Queensland fruit fly outbreaks around the Kyneton township this year. I heard about folks having infested tomatoes and apricots in town back in mid-January. In contrast, last year I was the only grower in the area with Queensland fruit fly, as far as I know. Am I the Typhoid Mary of Kyneton’s Queensland fruit fly outbreak? No, I’m just one of the few locals looking for and observing them. There were probably a lot of affected trees in town that slipped by unnoticed in 2024, and even more this year.

If numbers across the region are on the rise, then perhaps my relaxed approach hasn’t really resulted in an increase in Queensland fruit fly numbers. It’s not as though I have two identical netted enclosures where I’ve tried to control Queensland fruit fly in one and let it run rampant in the other. The challenge of understanding this pest in my own garden is the year-to-year variation in outbreaks.

My first summer (2023–24) with Queensland fruit fly was moderately warm, but rainfall in January 2024 was high. These subtropical conditions gave way to a warm and dry February and March.

My second summer with the pest (2024–25) was even more extreme. It was very hot and dry. Overnight temperatures were well above average, which is important when you consider Queensland fruit fly’s sunset temperature mating requirements. The extreme winds of both summers might have assisted their spread. However, the dry heat would have limited their ability to fly, and research shows that the adult flies can’t go without water for 48 hours.

So now I’m wondering whether this summer (2025–26) will be different:

- Will Queensland fruit fly baseline numbers continue to grow as they further establish themselves in the region? That is, if I continue to “do nothing” (well, very little other than make regular orchard inspections to remove infested fruit), will outbreaks continually worsen?

- Has Queensland fruit fly reached an equilibrium, meaning I’ll soon see an annual pattern of similar start and end dates of outbreaks develop?

- Was the summer of 2024–25 particularly well suited to Queensland fruit fly? In future years, when conditions don’t suit them so well (for example, when overnight temperatures are lower), will there be less Queensland fruit fly in my orchard than in early 2025?

What’s next?

I’m still trying to decide on my approach to Queensland fruit fly for the summer of 2025–26. I want to try one more year of relying solely on inspection and removal of infested fruit to help answer some of the above questions. But I also want to be a good neighbour and limit the spread. Plus, I’d really love to not have so much damage to my fruit in early autumn. It’s a tough call and I’m still deciding. In a future post I’ll discuss some of the control strategies available to backyard growers and explain which ones I’d consider best for my own situation.

What about you? What’s your experience with Queensland fruit fly? Please leave a comment below.

This is an important topic, so I am making it available to all readers, free and paid alike. Please share it widely with others battling Queensland fruit fly to give them hope and support.

Other resources on Queensland fruit fly:

Queensland Fruit Fly Part Two: Trapping, Baiting and Netting

Queensland Fruit Fly Part Three: Outside-the-box Strategies for Control

Eileen’s Queensland Fruit Fly Success Story

Queensland Fruit Fly Yarra Valley

Booklet: Fruit Fly Management for Fruit and Vegetable Growers